Conceptions of Curriculum

- Sarah

- Oct 10, 2022

- 3 min read

Why do some conceptions of curriculum continue to be used over time and are considered to be mainstream approaches, while others are not?

Curriculum approaches are ever-changing due to reasons that influence education like societal needs, culture and the interest of learners (Sowell, 2005). Despite the contradictory nature of the various curriculum conceptions, frameworks can contain a variety of curricular approaches, even simultaneously, due to the ongoing changes in social policies addressing the present and future, societal expectations, and the differences in viewpoints and philosophies of stakeholders like educators and school districts (Sowell, 2005, Ornstein & Hunkins, 2013). In the classroom, at the core of curriculum delivery, is the teacher’s interpretation of the curriculum’s purpose, which is directly impacted by their personal instructional methods, opinions and response to their student’s needs. When addressing questions of “what can and should be taught to whom, when and how?”, we must examine the context of the core curriculum conceptions of Eisner & Vallance’s (1974) and comparable conceptions of other curriculum theorists.

Curriculum Conception(s) | Contextual Highlights | To Use or Not to Use? |

Academic Rationalism |

| Vallance (1986) states this conception is likely to continue—this may be due to the construct of the education system as students require a set of knowledge to build on in upper grades, to pass exams, and further gain entry into post-secondary school. Academic Rationalism seems to be a “mainstream” approach. If this were to change, all levels of education “systems” would need revision. Controversy arises when the conceptions of curriculum are vastly different between education levels – for example, elementary versus high-school. Ensuring students are prepared for this change can be difficult when curriculum conceptions of teachers and leaders at each level differ significantly. Since this conception is what I remember of the education system when I was in school, along with my parents and grandparents, this seems to be a traditional, long-standing conception as Ornstein & Hunkins (2013) state. |

Social- Reconstruction- Relevance |

| This conception illustrates just how influential society is on curriculum and what people think should be taught, to whom and how. I foresee this curriculum conception gaining momentum again due to the rapidly changing world, race between countries for resources, and media and transparency into national and global decisions. Since there is a growing social responsibility of citizens, particularly after influential global events like COVID-19, the war in Ukraine, and climate change, this conception of curriculum will likely continue to be used, even if woven into other curriculum approaches. Social responsibility requires a level of understanding of global and national events, development of skills to analyze news and form opinions. The notion of “progressive” teaching being associated with this conception seems more like a mainstream instructional practice than part of a conception of curriculum. The conception itself seems like it could exist in conjunction with other curriculum approaches. Influential global events may cause this conception to re-emerge at certain times, and the context of events would impact whether an “adaptive” approach or “reformist” approach is taken (Sowell, 2005). This is not necessarily a mainstream approach, but rather driven by societal events to “provide the tools to enable the individual to survive and function effectively in an unstable and changing world” when needed (Al-Mousa, 2013, p. 24). |

Self-Actualization & the Humanistic Approach |

| These conceptions continue to be used throughout time, and will be considered more mainstream particularly in elementary level, as many teachers choose to teach to the “whole-child”. The time teachers spend with their students inevitably lends itself to teaching more than just subject matter. With access to technology, teachers can put the power of learning in their student’s hands and guide a more inquiry-based learning opportunity. Personally, I have experienced this powerful curriculum approach in my teaching career and witnessed the potential our young learners have and the ability to integrate all students to “provide personally satisfying experiences for individual learners” (Sowell, 2005, p. 42). Self-Actualization and the Humanistic Approach may grow in popularity once again due to the importance of these independent learning skills as the workforce adapts to societal changes, technological advances, and evolved skillsets. If teaching evolves to become more about teaching children how to use and inquire into the readily available information, this approach will compliment other conceptions. McNeil (2009) states that people persist, are more productive and responsible and self-aware learning through this approach – key skills for today’s technologically advanced children. |

Development of Cognitive Processes |

| This approach to curriculum compliments other curriculum conceptions and could continue to be used in conjunction with others versus viewed as an isolated conception. Since Al-Mousa (2013) defines this conception to address the question of “how” curriculum should be taught, students require a basis or foundation of the ”what” (knowledge and information) in order to develop their cognitive processes. |

Technology |

| Similar to Sowell’s (2005) beliefs, I believe curriculum as technology can no longer be viewed as an isolated conception. Our world has evolved to integrate technology into all aspects of our lives, including education. Technology will continue to be used, but as an instructional method of how to use curriculum in order to carry-out or integrate other conceptions of curriculum (i.e. inquiry-based learning, or even delivering material in an efficient way). |

Personal viewpoints and societal needs and expectations play such an impactful role in the rise and fall of curriculum conceptions. One’s geographic location, personal experiences, place of employment, student needs, and the state of the world provides conflicting expectations and opportunities that constantly challenge the curriculum’s purpose. Just like our world is evolving and responding to change, so is the curriculum. “Curriculum is never a final draft; revisions are always ongoing for purposes of improvement” (Pratt, 1994, as stated in Al-Mousa, 2013, p. 21).

As history revealed, society and policy will continue to impact mainstream curriculum conceptions. Influential events, educational studies and fads, national academic scores, and societal needs will all play a role in impacting the use (or elimination) of curriculum ideologies. On top of this, conflictions of personal viewpoints will continue to challenge curriculum conceptions. But regardless of the most current mainstream approach, as long as the curriculum remains open-ended, flexible and responsive to our future, there is space for educators to personalize rich learning experiences for their students.

I find myself considering the curricular conceptions on a continuum as Vallance (1986) suggests, accessing approaches based on need (student, society, subject, etc.) instead of policy, so not to limit learning opportunities. Eisner & Vallance (1974) remind us, “all ideas are not created equal, and some concepts and generalizations, some ideas and products of past inquiry are more useful and more profound than others” (p. 15). Based on my own personal viewpoints, preferences, values and personal/professional experiences, I find myself leaning towards the humanistic/ self-actualization approach with a “side of” academic rationalism. When I can, I weave in socially relevant topics to projects, integrate technology when possible and appropriate, and offer check-points in my students learning to reflect on their learning process. In order to educate all learners in their journey, it may actually be important for teachers to have flexibility with not only instructional practice, but also their professional curricular approach.

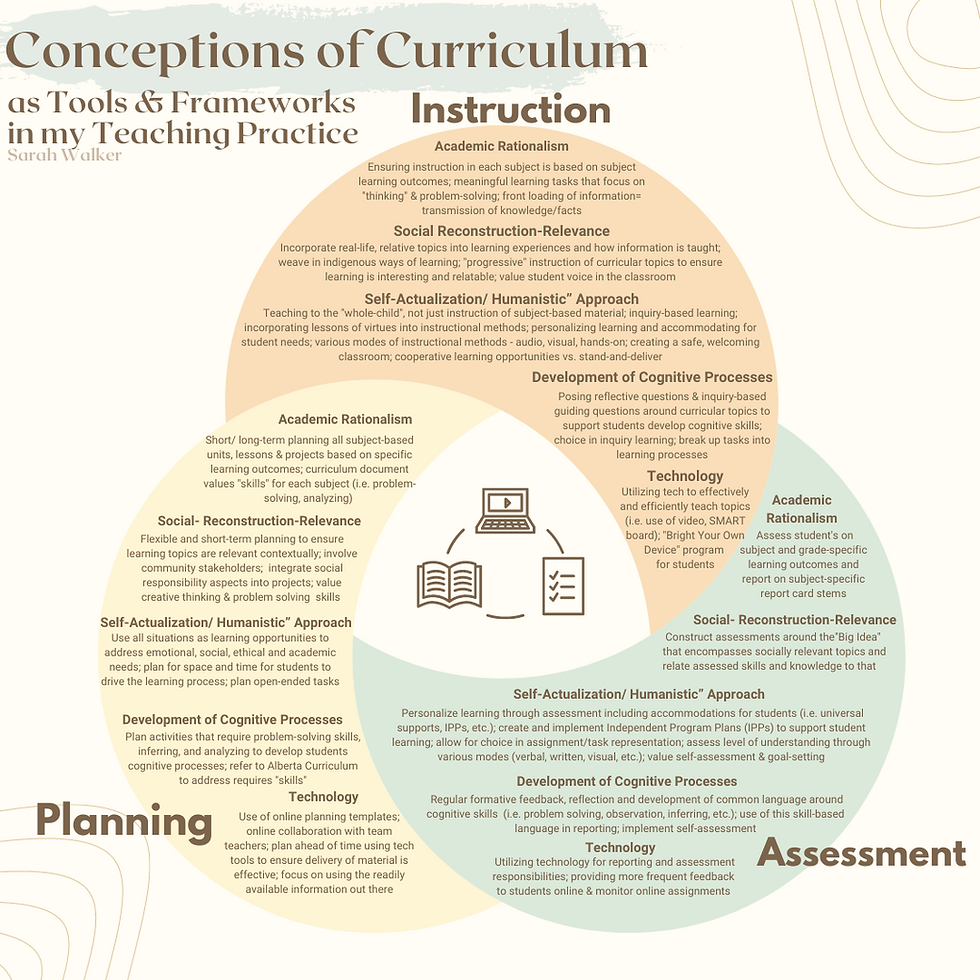

My interpretation of conceptions of curriculum and how I use them as tools or frameworks to analyze planning, instruction, and assessment within my teaching practice

While dwelling on various conceptions of curriculum throughout the many readings, I had time to reflect on my interpretations of each and how they trickle into my teaching practice - planning, instruction and assessment (or not). Previously, I mentioned how I resonated with Vallance’s (1986) suggestion of reorganizing the conceptions on a scale-like continuum. I can see how I shift on this curriculum conception scale within my context of practice as an elementary teacher. Depending on the subject, grade, time constraints, expectations from my school board, school philosophy, societal and community needs, and student learning abilities and needs, it is my interpretation that the various conceptions of curriculum actually work together as building blocks to grow my professional practice into what it is. Focusing on the five curriculum conceptions of Eisner & Vallance (1974) and comparable conceptions of other theorists, I organized my initial reflections in a visual of how I use them as tools or frameworks within my teaching practice.

References

Al Mousa, N. (2013). An examination of cad use in two interior design programs from the perspectives of curriculum and instructors, pp. 21-37 (Master’s Thesis).

Eisner, E., & Vallance, E. (Eds.). (1974). Five conceptions of the curriculum: Their roots and implications for curriculum planning.In E. Eisner & E. Vallance (Eds.), Conflicting conceptions of curriculum (pp. 1-18). Berkeley, CA: McCutchan Publishing.

McNeil, J. D. (2009). Contemporary curriculum in thought and action (7th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley. Pages 1, 3-14, 27-39, 52-60, 71-74.

Ornstein, A. C., & Hunkins, F. P. (2013). Curriculum: Foundations, principles, and issues (6th ed.). Boston, MA: Pearson. Read part of Chapter 1, pp. 1-8.

Sowell, E. J. (2005). Curriculum: An integrative introduction (3rd ed., pp. 37-51). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.

Vallance. (1986). A second look at conflicting conceptions of the curriculum. Theory into Practice, 25(1), 24-30.

Comments